It’s just so hard to break dogma in medicine these days, but those in the regular practice of wilderness care or prolonged patient transport are happy to see the use of the ubiquitous rigid spine board fade away.

Even in New York City we are leaving this practice behind

Why?

Application of spinal precautions in a wilderness setting can lead to unintended consequences

What is the evidence against the rigid board?

Placing a patient in spinal immobilization can adversely affect breathing and airway management. American Heart Association 2010 evidence-based guidelines state that “Routine c-spine immobilization is a Class III (potentially harmful) unless clear trauma is evident in the history or exam, because it may unnecessarily delay or impede ventilations.” One study conducted on healthy volunteers showed that placing a patient on a backboard restricts respiration, with older patients having a greater degree of restriction.

Studies have shown that C-spine collars cause increased intracranial pressure, which may be clinically significant for patients with head injuries. Therefore hard cervical collars should be removed immediately after exclusion of a C-spine injury, especially among patients with head injuries.

C-spine collars are also contraindicated in patients with penetrating neck injuries, because they may interfere with management of neck wounds or even conceal these wounds. Penetrating wounds to the spinal cord are rare. Cervical immobilization creates the real possibility of causing greater morbidity than protection.

In addition, pressure ulcers are very painful complications from spinal immobilization. Pressure ulcers begin forming within 30 minutes of immobilization. This is particularly troubling as another study demonstrated that the mean time patient spends on a backboard can exceed two hours in urban settings. This time is likely protracted in wilderness settings.

Combine all this with the fact that there isn’t a single prospective, randomized controlled trial on spinal immobilization demonstrating benefit.

Several states and EMS systems around the nation are, therefore, beginning to use protocols to help decrease the number of trauma patients being subjected to prehospital spinal immobilization.

The guidelines that have been adopted by multiple prehospital systems are typically based on the Canadian C-spine rule and the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS) low-risk criteria.

Summary of NEXUS Criteria on Imaging Spinal Cord Injuries. No imaging is necessary if all of the following are present:

- No posterior midline cervical tenderness

- Normal level of alertness

- No evidence of intoxication

- No abnormal neurologic findings

- No painful distracting injuries

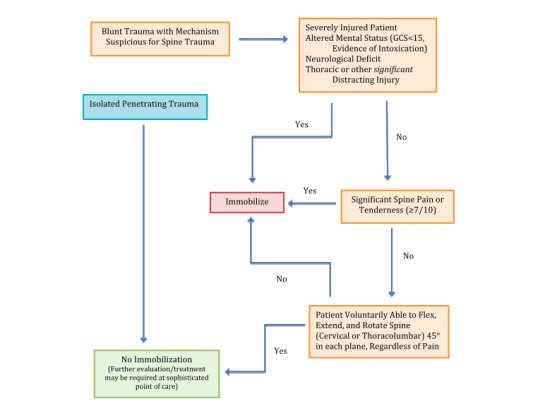

For the wilderness setting, a similar guideline has been recently proposed. The treatment algorithm was specifically calibrated so as to minimize risk of exacerbating a potentially unstable spine injury weighed against the risks to rescuers and victim in the austere setting.

REFERENCES

Berg RA, Hemphill R, Abella BS, et al: Part 5: Adult basic life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care, Circulation 122(18 Suppl 3), 2010.

Totten VY, Sugarman DB: Respiratory effects of spinal immobilization, Prehosp Emerg Care, 3(4):347, 1999.

Hunt K, Hallworth S, Smith M: The effects of rigid collar placement on intracranial and cerebral perfusion pressures, Anaesthesia 56:511, 2001.

Haut ER, Kalish BT, Efron DT, et al: Spine immobilization in penetrating trauma: More harm than good? J Trauma 68:115, 2010.

Cooney DR, Wallus H, Asaly M, Wojcik S. Backboard time for patients receiving spinal immobilization by emergency medical services, International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 6:17, 2013.

Hoffman JR, Mower WR, Wolfson AB, Todd KH, et al: Validity of a Set of Clinical Criteria to Rule Out Injury to the Cervical Spine in Patients with Blunt Trauma, New England Journal of Medicine 343:2, 2000.

Quinn R, Williams J, Bennett B, Stiller G, Islas A, McCord S: Wilderness Medical Society Practice Guidelines for Spine Immobilization in the Austere Environment, Wilderness Environ Med 24, 241, 2013.