LESSONS LEARNED FROM BEING BURIED ALIVE.

THE TAKE HOME

Survival of avalanche burial > 30 mins does happen

Maintain a sense of urgency in all avalanche rescues until the

victim is found

INTRO

‘I heard what sounded like a baseball bat hitting a ball – a loud crack. I turned around to look and saw a feathery white cloud of snow heading for us . .

After being buried, as soon as I could, I tried to push my hands out away from my face. They didn’t go very far. I tried to raise myself up, tried to lift my head up, but nothing would give. I didn’t know if there was someone who could find and help me. I didn’t know if anyone else was dead or alive. I couldn’t move. I tried to not panic. I knew if I did, I would use up the air that I had, really quick.’

L. M., avalanche survivor. *with permission

In February 2014 in south central Idaho, all four members in a snowmobiling party were completely buried in a destructive force size 3 avalanche. What ensued was an improbable tale of 3 survivors. One particular woman lived to tell the tale above. Rescued by a team of bystanders from the community arriving late to the scene, she endured a burial lasting over 90 minutes.

Figure 1. View of the 16 Feb 2014 Idaho avalanche from the top of the debris field. (Savage 2014, Sawtooth Avalanche Center photo).

I think the tale conveys important points to keep in mind that we’ll review below. Whether you are a professional rescuer or a bystander called upon to assist on a burial, we ask that you pack along this food for thought with you.

SURVIVAL HAPPENS

When they told me how long I had been buried – at least an hour and a half, I was in disbelief. I had no concept that it had been that long. This leads me to think that maybe I passed out for a while, but I don’t know.

— L.M.

Figure 2. View of L.M. recovery site. She was successfully recovered from this spot after buried for 104 minutes. (Savage 2014, Sawtooth Avalanche Center photo).

I was notified of the Idaho incident through EMS dispatch. Having heard reports that companion rescue was not successful, and at least one other victim remained buried one hour after the slide, I assumed a body recovery would ensue. Colleagues admitted to a similar pessimism at the time. As it turns out, 3 individuals each survived burial longer than 40 minutes.

I had mentally resigned that someone was dead, while they were still struggling to survive. It was a clear call to challenge a few of my own assumptions and look to the data.

In fact, since 2000, 9 people have survived burials of 4 hours or longer in the US alone.,

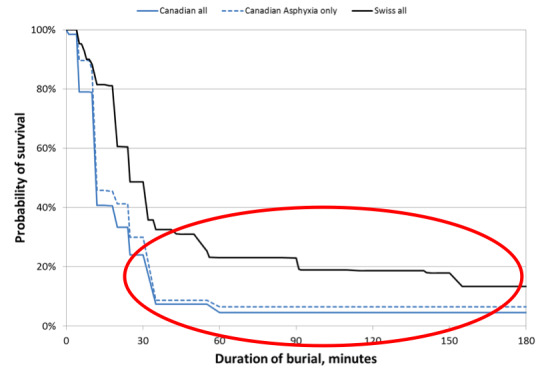

A closer inspection of the same data that drives our bias reveals that ‘slim chance’ does not mean ‘no chance’. In review of our most robust avalanche survival data set to date, one discovers that burial over 35 minutes does not mean 0% chance of survival, but perhaps anywhere from 5-20% chance of survival.

Figure 3. Red circle depicts ranges of anticipated survival rates in prolonged burial >35 mins. (adapted from Savage 2014 with reference data Haegli et al 2011).

The avalanche community has done an excellent job educating recreationists, professionals, and educators that we must find buried victims in the initial 15-30 minutes or they probably will not survive. While this tactic deserves respect and is evidence based, perhaps it has unintentionally led us to assume that all rescue operations extending beyond 30 minutes will be futile. In my subsequent discussions with Savage, Atkins and other professional colleagues we shared a collective observation and experience that rescuers’ attitudes, intensity, and speed change as rescues become protracted.

So perhaps it’s time to consider changing a few of those assumptions.

BURIED AND BREATHING

I scratched again, had a little snow come down and saw a little more light. It was then that I felt a little cold air come in also. At that point, I quit scratching, afraid I would pull too much snow down and plugging up what tiny bit of air I had gotten.

– L.M.

What factors are thought involved in survival as burial time progresses?

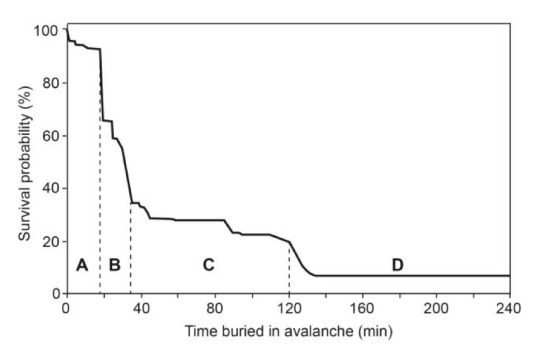

Figure 4. An example of avalanche survival curve showing the survival phase (A), asphyxia phase (B), latent phase (B) and long-term burial phase (D).

In the survival phase (A), survival remains high and deaths occur primarily from trauma. In the asphyxia phase (B), there is a precipitous drop in survival rates due to lack of a patent airway. In the latent phase ©, survival does not change drastically and reflects the survival of victims with patent airways, although for a limited time. In this phase survival gradually decreases and deaths occur from the insidious impacts of hypothermia, limited oxygen, or accumulation of carbon dioxide. In the long-term burial phase (D), long-term survival is possible in a very low percentage of victims if oxygen support is sufficient. The duration of these phases and associated survival probability differ between regions, partially due to geographic and climatic factors but also to rescue procedures. (ie early CPR, rapid evacuation, access to trauma center or cardiopulmonary bypass)

The comments of our survivor above and the details of her case support that she survived, likely due to a combination of a patent airway, a lack of significant trauma, and adequate airflow to prolong her survival through the latent phase.

But the question remains. How would a rescuer ever know if the presumed victim has a patent airway, no bad trauma, and adequate airflow to sustain a prolong burial and make rescue successful? What’s the chance they may be one of the lucky 10%? Without going to look … well you would never know. And yet, I fear at times we assume that it’s a lost cause without going to take a peek.

Are we unfairly triaging the patient before we even lay eyes on them?

FINAL THOUGHTS

‘I know that I was getting close to giving up. Then all of a sudden I heard a snowmobile drive up. …, I heard a voice yell “I’ve got her”. I heard the shovel come into the snow and I don’t know what I said or yelled, but I guess I scared the poor guy to death. He was not expecting to find me alive.

— L.M.

Assume you’re on patrol on a god forsaken day of low vis and snot snow, indulging in your 6th cup of joe at the tram deck. A massive man waddles over in his rear entries with eyes bulging, sweat beads rolling down his forehead, he then clutches his chest with his pale hand and drops to the floor. Sure it’d be great if he didn’t double up on the bacon with every cheeseburger and chase every martini with a cuban cigar. It would be nice if the defibrillator wasn’t up at the top shack, but I doubt you’re going to carry any hesitation in starting chest compressions ASAP. And what are the odds he’s gonna pull out of this okay? Well in one robust data set of 417,000 out of hospital cardiac arrest patients, only 9.6% actually survived to discharge from the hospital. This includes those that suffer severe disability.

So now imagine responding to a avalanche accident, looking out over that slide path. Sure it would be nice if that party decided not to head out on a red light day. Perhaps it wasn’t a good idea for them to cross the wind loaded slope. Of course it would have been better if they could have been proficient enough to rescue their partner. But just because you’re there 45 minutes later, is all hope truly lost? What does the survival curve say? It may be no worse than that cardiac arrest case we channel so much urgency into.

I don’t intend to suggest that we’re all lazy, overly pessimistic, or cynical when it comes to buried victims. Perhaps it’s a simple psychology of out of sight out of mind. Maybe we fail to be adequately emotionally invested, because we can’t look our patient in the eye. Buried under all that white rubble, they can’t show us how much they need help. We have no idea how close they are to giving up.

Figure 5. Don’t resign to ‘already dead and buried?’, Ask yourself ‘Is there any chance they could be buried alive?’

I’m not advocating for a hasty response at reckless abandon and hazard to ourselves; but let’s do our best to not write an obituary before heading to the debris pile.

Think of the survival curve.

Uncover and lay eyes on your patient.

Tell me what you find. We can talk what happens from there with your patient on future posts . .